The author sent me an autographed copy of his novel to review:

Benjamin Dancer writes a fast paced novel that rivals and apes Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity. Both main characters are government agents of some sort suffering from extreme memory loss. The author claims that this novel is part of The Father Trilogy (this being the third book), but this reviewer had to stretch his imagination to think that this novel had anything to do with being a father. I’m not saying that I didn’t enjoy this expeditious page turner, because I did; however I did find some minor flaws, mostly involving gunfire that I’ll talk about later. I think authors that write espionage novels, such as Tom Clancy’s Clear and Present Danger (1989) and Red Storm Rising (1986), make sure there isn’t any continuity errors, especially involving weapons. I’ve read and seen many films that suffered from this malady. Anyway, that being said, this novel almost takes your breathe away, and that is a good thing. I’m a big fan of short chapters and cliffhangers, and Benjamin Dancer specializes in both elements. I found the story a little provocative since the reader wants to know right away what Jack Erikson (our protagonist?) has stashed away and when he will remember where it is. Okay, enough said, how about the story?

A bomb goes off on a vehicle procession in Washington, D.C., Jack Erikson finds himself wounded, handcuffed, bewildered, amnesiac and pursued by a man with an MP5 submachine gun. Somehow Jack escapes and finds his way to Colorado by instinct (why are other reviewers talking about West Texas?). He finds his son Billy, whom he hasn’t seen in ten years. Killers in black vehicles attack Jack and his son. The villains (are they?) die after an intense gun battle with Jack and Billy. Meanwhile, Jack’s wife Rachel is kidnapped. Who are these people, and what do they want? They seem to think that Rachel knows where Jack is (she hasn’t seen him in ten years) and where he has hidden what they want. Got it so far? Later we find out that Jack stole something from the Chinese and is now being chased by a hired group of Mexican Special Forces, an unnamed USA government agency and by Jack’s ex-boss, a slightly discombobulated Colonel. Billy gets separated from Jack and gets rescued by the authorities and turned over to Sheriff Regan, who is Rachel’s lover. While the Sheriff tries to get Billy to safety, they are attacked by the Mexicans. In a brutal gunfight, the Sheriff and the Mexicans die, while Billy escapes. Don’t think that I’m giving the plot away, because all of this occurs early in the novel. Now Jack tries to free his wife from the kidnappers. He still doesn’t know what’s going on. And I’m not sure who are the good guys or who are the bad guys. Anyway, Mr. Dancer, your writing is first-rate hiding the good, and the bad from the ugly (sounds like a movie).

I thought the novel should’ve had more flashbacks pertaining to Jack and Rachel’s initial encounters, which were interesting, in lieu of all that gunfire. Have faith in your prose; it’s very good. More background or flashbacks on the characters would have added more beef to the story. For instance, Rachel had a ten year relationship with the sheriff and the reader learns almost nothing about it. And what did the Colonel mean on page 262, when he said, "Your dad spent much of the last decade in a prison very few people have heard of." What I’m trying to say is the novel could’ve had a lot more meat on the bones. You had some great ideas, but didn’t follow up on them. These minor defects stopped this very good novel from being great. By the way, as an ex-Marine on a rifle and pistol team, I can tell you that it is impossible to shoot a paper plate at two hundred yards with a service revolver (page 88). I know my review sounds critical, but I did enjoy this novel, even though the war/terrorism genre is not my normal cup of tea. Could have it been better? Yes, but there aren’t that many Clancys, Flemings or le Carres out there. I highly recommend this thriller novel, especially to all the espionage fans.

RATING: 4 out of 5 stars

Comment: I wanted to talk about Benjamin Dancer’s first two books in his trilogy, In Sight of the Sun, and Fidelity, but couldn’t find anything about those books on Amazon, Goodreads, or the internet. I’ll have to email him to find out why. Therefore, lets talk about the two Tom Clancy novels I mentioned in the first paragraph:

Clear and Present Danger (1989): Goodreads says, “CIA man Jack Ryan, hero of Patriot Games, finds that he will probably never have a boring summer: The sudden and surprising assassination of three American officials in Colombia. Many people in many places, moving off on missions they all mistakenly thought they understood. The future was too fearful for contemplation, and beyond the expected finish lines were things that, once decided, were better left unseen. Tom Clancy's new thriller is based on America's war on drugs.”

Red Storm Rising (1986): Goodreads says, "Allah!"

“With that shrill cry, three Muslim terrorists blow up a key Soviet oil complex, creating a critical oil shortage that threatens the stability of the USSR.

To offer the effects of this disaster, members of the Politburo and the KGB devise a brilliant plan of diplomatic trickery - a sequence of events designed to pit the NATO allies against each other - a distraction calculated to enable the Soviets to seize all the oil in the Persian Gulf.

But as this spellbinding story of international intrigue and global politics nears its climax, the Soviets are faced with another prospect, one they hadn't planned on: a full-scale conflict in which nobody can win.”

I didn’t mention it before, but my favorite Clancy novel is The Hunt for Red October (1984):

Goodreads says, "Here is the runaway bestseller that launched Tom Clancy's phenomenal career. A military thriller so gripping in its action and so convincing in its accuracy that the author was rumored to have been debriefed by the White House. Its theme: the greatest espionage coup in history. Its story: the chase for a top secret Russian missile sub. Lauded by the Washington Post as "breathlessly exciting." The Hunt for Red October remains a masterpiece of military fiction by one of the world's most popular authors, a man whose shockingly realistic scenarios continue to hold us in thrall. Somewhere under the Atlantic, a Soviet sub commander has just made a fateful decision. The Red October is heading west. The Americans want her. The Russians want her back. And the most incredible chase in history is on…”

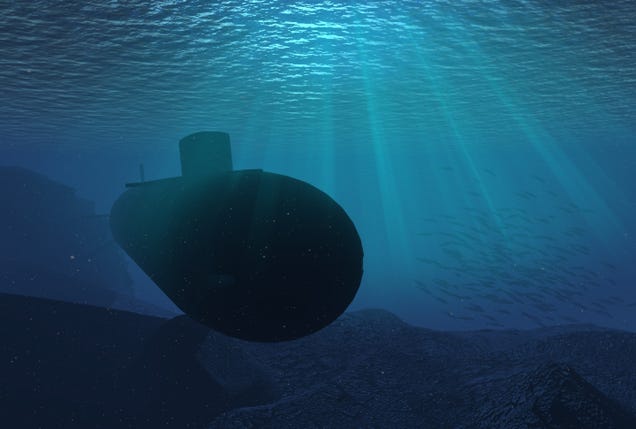

The Russian sub heading west: